Designing and Reviewing Informed Consent in Clinical Trials Pdf

- Review

- Open Admission

- Published:

The reality of informed consent: empirical studies on patient comprehension—systematic review

Trials volume 22, Article number:57 (2021) Cite this article

Abstract

Groundwork

Informed consent is a basic concept of gimmicky, autonomy-based medical practice and facilitates a shared decision-making model for relations between physicians and patients. Thus, the extent to which patients tin comprehend the consent they grant is essential to the ethical viability of medicine as it is pursued today. Even so, research on patients' comprehension of an informed consent'due south basic components shows that their level of agreement is express.

Methods

Systemic searches of the PubMed and Web of Science databases were performed to identify the literature on informed consent, specifically patients' comprehension of specific informed consent components.

Results

In full, fourteen relevant articles were retrieved. In most studies, few clinical trial participants correctly responded to items that examined their awareness of what they consented to. Participants demonstrated the highest level of understanding (over 50%) regarding voluntary participation, blinding (excluding knowledge nearly investigators' blinding), and freedom to withdraw at any time. Only a small minority of patients demonstrated comprehension of placebo concepts, randomisation, safety bug, risks, and side effects.

Conclusions

We found that participants' comprehension of central informed consent components was low, which is worrisome considering this lack of understanding undermines an ethical colonnade of gimmicky clinical trial practice and questions the viability of patients' full and genuine involvement in a shared medical decision-making procedure.

Introduction

Written informed consent (IC) is considered a basic principle of medical do. Information technology provides data and shares knowledge between the medico and patient and creates a shared-decision-based healthcare programme [1]. In this regard, the IC should implement a principle of autonomy, past which a patient's correct to deliberately decide for herself whether to accept or reject the offered treatment must be respected [2, 3]. Nevertheless, patients' adequate understanding of the provided information is a major limitation.

Within its ethical and legal foundations, the informed consent procedure is pivotal to supporting ethically audio medical intervention. However, obtaining adequately informed consent from patients is complex because it requires homo interactions involving give-and-take of several elements, such as the patient's status and therapeutic options, including risks and benefits, inconveniences, and uncertainties. In this regard, IC must include both a grade that patients are required to read and sign, and speech to ensure acceptable understanding to facilitate voluntary willingness to participate in a clinical trial [4].

Major barriers to adequate IC agreement include the patients' subjective impression that they are well informed and physicians' over-conviction in the intelligibility and quality of the information they provide to patients. Nonetheless, the concept of respecting patients' autonomy in medical research is based on the assumption that the informed consent process actually leads to patients' full comprehension of what they are consenting to. Unless this assumption is demonstrably true, the ethical viability of the current medical experimentation practice is seriously flawed.

Given that near available studies focused on informed consent obtained for the purpose of clinical trials, nosotros limited our scope to this kind of inquiry practice. However, there is no reason to assume that the level of understanding of informed consent granted by patients in a routine medical practice is significantly college than that in clinical trials. On the contrary, we find it plausible that patients recruited to clinical trials are relatively meliorate informed and physicians may explain the nature of a research intervention and participation conditions more thoroughly. Therefore, it is improbable that patients' actual comprehension of consent in standard medical practice is higher than in the relatively amend examined conditions of clinical trials, and there are reasons to look that it is lower. With this reservation, our conclusions may be extended across clinical trial weather condition to the more general do of obtaining informed consent in medical practice.

Therefore, we systematically reviewed the available literature on patients' bodily (rather than declared) understanding of what they consented to, with item interest in questionnaires developed to objectify patients' understanding of the consent content, rather than their subjective impression on how well informed they were during the consenting process, and whether they were satisfied with the way in which their consent was obtained.

Methods

We performed a systematic review using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) criteria [five]. The electronic search to place and capture informed consent literature was conducted between October 2019 and January 2020. We queried PubMed and Web of Science databases using the post-obit search terms: "informed consent [mh] AND (comprehension [mh] OR perception [mh] OR knowledge [mh] OR conclusion making [mh] OR agreement OR advice [mh]) AND (randomised controlled trials as topic [mh] OR clinical trial as topic [mh])". No year restrictions were practical. To make the search every bit comprehensive as possible, we used the Boolean operators "AND" and "OR" to link the search terms.

Inclusion criteria were (a) studies assessing comprehension of IC, (b) English-language manufactures in peer-reviewed bookish/scientific journals, (c) full-text manufactures bachelor electronically, and (d) articles with available questionnaires used to examine the level of patients' understanding.

Exclusion criteria were (a) studies comparing or evaluating methods of informed consent not related to IC comprehension (defined in inclusion criteria), (b) studies that used intervention to improve patients' understanding, (c) studies that included patients with cognitive refuse, (d) qualitative research, (e) manufactures based on patients' impression of agreement, (f) studies based on interviews, (g) studies that did non provide the questionnaire used, (h) conference abstracts, and (i) animal studies.

We included just manufactures that examined knowledge about the information included in the IC. In this regard, we excluded articles based on interviews and questionnaires that examined just patients' impressions of understanding (e.g. "Did yous receive acceptable information about the study?").

Article choice was performed independently by the first (TP) and 2d (KS) authors. Database searches were completed in a blinded manner using identical search terms. After identifying eligible articles, any doubts were resolved during a meeting to review the queried article(s) against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The final selection of eligible manufactures included in the critical appraisals was made based on the agreement betwixt TP and KS.

Results

Option process

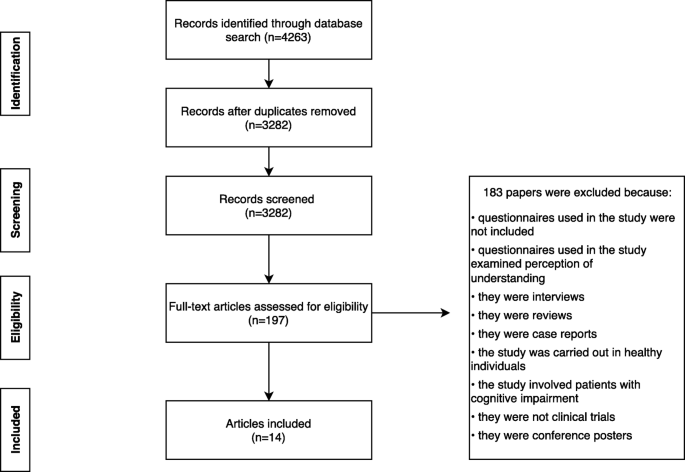

The written report option process is shown in Fig. 1. In total, 4263 articles were retrieved from the databases, of which fourteen were included in the review based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria (Table i). The number of participants varied beyond studies, ranging from 29 [16] to 1835 [9]. In most studies (n = 12), participants were adults [vii,8,9,x,11,12,13,fourteen,xv, 17,18,19]; three studies examined parents or guardians [6, 10, 16]; and one written report included both adult patients and parents or guardians [10]. Medical specialties included communicable diseases in 42% (north = 6), including vaccine studies in 21% (north = iii), oncology in 28% (n = 4); rheumatology in 21% (n = 3); neurology in 7% (n = 2), and others in 7%. Two studies included clinical trials in more than i specialty [viii, xv]. Most studies examined IC-related questions that covered bounty, withdrawal criteria and consequences, report versus treatment, written report administration, and randomisation.

Selection process for eligible articles

Understanding of informed consent

Questionnaires that examined participants' understanding of IC components included true/imitation items [9, 10, 18], multiple selection items, and the Quality of Informed Consent survey [7, 11]. Questionnaires differed in the number of items and content. All questionnaires examined participants' call up of IC content, except one, where participants used the IC text to find the answers to the survey questions [xix]. Additionally, the elapsed fourth dimension between participants' feel of the informed consent process and their IC research participation ranged from before the actual IC [18] process to 5 years after the IC [fifteen]; four studies did non study this measure [8, 12, 16, 19].

Three studies examined participants' understanding of the research purpose. Schumacher et al. reported that all participants understood that they were participating in a research study and recognised its purpose [seven]. In the remaining 2 studies, almost participants comprehended the written report aims (70–xc%) [nine, nineteen].

Voluntary participation was examined in seven studies [6,7,8,9, 11, 13, 14]. Bergenmar et al. reported the highest level of comprehension, with 96% of participants comprehending the voluntary nature of their participation [xi]. In dissimilarity, Chu et al. reported the lowest level of comprehension, with 53.six% [8]. Additionally, Krosin et al. noted a significant deviation between urban and rural participants, with 85% and 21%, respectively, showing comprehension of the voluntary nature of participation [13]. Chu et al. reported that 53.six% patients understood that physicians should not persuade them to participate in a study [8]. Criscione et al. reported that ten% of participants indicated that their personal dr. would mind if they dropped out of the report [xiv].

Freedom to withdraw was reported in viii studies [6,7,viii, 10, 12, 14, 17, 19], which was a relatively well-comprehended IC component, with the everyman level of 63% reported by Criscione et al. [14]. Ponzio et al. reported that all participants correctly understood their right to withdraw at any time [xix]. Additionally, one written report reported on awareness of withdrawal consequences, with 44% demonstrating comprehension of this point; and withdrawal criteria, with only ten% showing comprehension [xiii].

Comprehension of randomisation was investigated in seven studies, with Harrison's report reporting the highest level of understanding (96%), and Bertoli et al. reporting the lowest (10%) [8, 11, 12, 14,15,16]. Similarly, the understating of placebo and active handling ranged from thirteen% [15] to 97% [9]. Differences by specialty regarding comprehension of the placebo concept were noted by Pope et al., with the lowest comprehension reported in the ophthalmology group (13%) and the highest in the rheumatology group (49%) [xv].

Risks and benefits were explored in nine [half-dozen, 7, nine,ten,11, xiii, 14, 18, 19] and three studies [6, 7, 19], respectively. Krosin et al. reported that but 7% of patients comprehended risks associated with involvement in clinical trials [thirteen]. In contrast, in one group, all patients (who could use the IC text to find questionnaire answers) were aware of potential side effects and risks of the treatment [19]. Ponzio et al. reported the highest betwixt-group differences in the comprehension of study benefits, which ranged from 35.5 to 96.6%, depending on whether participants were successful in finding the answer in the IC text [19].

It is worth noting that Schumacher et al. reported that patients were non enlightened that the proposed treatment was experimental and not standard therapy [vii]. Additionally, only 20% of participants understood that the benefits of treatment were uncertain and that participation was associated with boosted risks. Similarly, over xxx% of patients were not aware that alternative treatments were bachelor.

Furthermore, Chu et al. found that only 43.4% of patients understood that they would non exist reimbursed for all adverse events related to the report. Of note, the authors did non specify the weather regarding reimbursement. The number of correct responses was college in the good for you control group than in the patient group (excluding the last question related to reimbursement) [8].

Finally, Bertoli et al. reported that 86 participants (83.five%) recalled that they had fully read the informed consent grade, while xi.7% had partially read information technology and ix% did non recall to what extent they had read it. Interestingly, most patients (51.4%) rated their knowledge almost the report as high, but objective evaluation of participants' noesis showed that only xiv.3% demonstrated a high level of knowledge, and 58.1% and 27.half dozen% showed intermediate and low knowledge, respectively [12]. Pope et al. reported that 18% of participants admitted that they had not fully read the report information letter and 10% admitted that they were afraid to enquire questions [fifteen].

Assessment of take chances of bias

Studies included in this review were either randomised nor blinded for the outcomes related to IC. Therefore, the assessment of risk of bias was not possible [xx].

Discussion

We ended that there are significant discrepancies in research participants' understanding of voluntary participation, blinding, and freedom to withdraw. Only rarely did all participants respond correctly to questionnaire items, indicating that they actually comprehended what they consented to. We plant that participants presented the highest level of understanding (over l%) about voluntary participation, blinding (excluding cognition about investigators' blinding), and freedom to withdraw at whatsoever time. Further, our results suggest that only a small minority of patients had a clear and accurate understanding of all aspects of their consent. In item, patients presented significant difficulties in grasping the concept of placebo randomisation, safety, risks, and side effects [seven,eight,9,10,11,12,xiii,xiv,15,16, 18, nineteen]. Additionally, some patients had very limited comprehension of the research benefits [vi, 19].

Our findings are consequent with the results of previous meta-analyses on the quality of the informed consent process in clinical trials [21]. Even so, in general, patients included in our review demonstrated lower levels of comprehension. Tam et al. [21] reported that two-thirds of participants (the highest reported level) understood the freedom to withdraw from a study at whatsoever time, followed past the nature of the study, the voluntary nature of participation, and the potential benefits. In contrast, our results showed that 69.vi% of participants understood the purpose of the report and just 54.ix% could name at to the lowest degree one risk. Finally, approximately half of the participants understood placebo and randomisation concepts. Nevertheless, in contrast to our review, Tam et al. included data from interviews in their analysis. Surprisingly, in 58.5% of interviews, participants could non establish whether the interviewers were investigators in the original clinical trial and, as such, could influence the results [21]. In a previous systematic review of clinical trial IC or surgery IC, Falagas et al. concluded that simply 50% of participants properly understood all IC components [22].

These findings demonstrate that crucial information, including risks and benefits, voluntariness, and the relation of trials to standard therapy, are not actually comprehended by a substantial number of participants. This seriously undermines the present practice of providing a sound ethical footing for experimenting with human subjects. Moreover, it seems that patients' understanding of specific IC components has not changed over the past xx years [21]. The guidelines for skillful clinical do in trials, introduced past the Globe Health Arrangement 20 years ago, have non affected patients' comprehension [21, 23].

It is natural to expect a correlation between general health literacy and comprehension of information relevant to informed consent. The extent to which deficits in understanding consent depend on bereft general health literacy remains to be examined. However, this may not exist crucial to the existing practise viability in obtaining informed consent as a safeguard for respecting patients' autonomy in clinical trials. Information technology is inevitable that patients recruited for clinical trials will have varying pedagogy and health literacy levels. There is no reason to presume that patients included in clinical trials take lower than boilerplate wellness literacy. Therefore, the outcomes suggest that, in the daily practice of clinical trials, patients with diverse pedagogy and health literacy levels agree to participate in medical testing based on defective, or at to the lowest degree incomplete, comprehension of the relevant information. This suggests that the present routines regarding patients' autonomy (and thus—dignity) in clinical trials are ethically questionable, if not explicitly flawed.

None of the studies included in our review directly examined relations between patients' health literacy and their level of comprehension regarding the consent they granted. However, Chaisson et al. reported that patients' educational activity was considered every bit a gene potentially influencing their understanding of the consent. They administered questionnaires in English or Setswana and concluded that participants who had a college pedagogy level or chose to complete the questionnaires in English language rather than Setswana demonstrated better overall comprehension. Similarly, Schumacher et al. and Krosin et al. found significant correlations betwixt comprehension scores and formal pedagogy levels [7, thirteen]. Ellis et al. distributed a survey to adult participants in the Us and Mali, plus the parents or guardians of a kid in an additional group of Mali participants. Within Malian adults, only 9% signed the IC, while the remaining 91% provided a fingerprint. In the Malian parents or guardians grouping, 84% provided a fingerprint rather than a signature. The literacy rate for parents or guardians varied between sites, ranging from 3 to 17%. Of note, the questionnaire was initially intended to teach participants rather than to collect data [x]. The researchers constitute that patients' literacy was not a significant cistron in their ability to empathise the consent they were asked to grant.

The studies included in this review accept some limitations that should be considered while interpreting the results. Outset, they demonstrated a high level of heterogeneity in sample size and type of underlying medical condition. Nosotros speculate that this may also have influenced patients' understanding of informed consent. For example, Pope et al. reported significant differences in the level of understanding inside patients recruited to rheumatology, ophthalmology, and cardiology studies [15]. Similarly, Chu et al. reported that 61% of salubrious controls were recruited from phase I trials, in which they were nether the close monitoring and care of the researchers, while 80.viii% of patients were recruited from phase Iii or 4 trials that were conducted in outpatient clinics [8]. Second, particularly in oncology, the presumed potential benefit of a novel treatment may exceed the presumed risk of the written report, biasing patients towards consenting to participate in the trial despite a limited understanding of its experimental nature. Third, although education level was usually mentioned, health literacy was non examined in most studies. Additionally, other factors related to underlying illness may influence patients' comprehension, including fatigue, depression, cognitive status, and emotional factors associated with study inclusion and doctor'southward office visits. The resulting scope of interference with patients' power to grasp the full meaning of the consent remains unexamined. Even so, such factors should be considered when assessing the current practice of obtaining informed consent. Finally, the scales used to examine patients' understanding differed across studies and ranged from multiple option to Likert-like calibration items, which limited our ability to fairly compare patients' agreement across studies.

In many cases, patients may be unaware that they lack understanding and therefore practise not ask for clarification. In some cases, the information on expected therapeutic benefits may overshadow other aspects of the projection, making patients less receptive to technical or more than discouraging sides of the trial. Interestingly, our findings suggest that mothers asked to consent to including their children in a clinical trial were more than determined to comprehend all relevant information than adult patients deciding on their ain interest in a trial. Notwithstanding, this is based on the results from a single study in this review [6].

The relatively consequent series of empirical findings opens further questions that have non been satisfactorily addressed in the literature to date. We hypothesise that patients seriously overrate their ain level of comprehension. The extent to which they mistakenly experience that they take understood all relevant information while, in fact, they miss many important aspects of the consent present an interesting question that we are preparing to investigate. Similarly, physicians may seriously overrate their patients' level of comprehension based on (1) their own efforts to effectuate patients' agreement, (2) their conviction in patients' proclamation of understanding and satisfaction, and (3) their own health literacy influencing their belief that the information offered to patients is easier to empathise than is really the case.

Thus, further research should target empirical testing of the hypothesised discrepancies between (1) the actual level of understanding past patients regarding what they consented to, (2) their subjective confidence that they understood what they consented to, and (3) physicians' confidence that their patients actually understood what they consented to.

Noting the scarcity of analogous research on the actual agreement of consent by patients in regular therapeutic practice, nosotros recommend that future studies examine such comprehension in ordinary medical settings rather than only through the context of clinical trials. Since physicians typically take more care and effort to explain all relevant aspects of a clinical trial, we assume that, in a standard therapeutic setting, lack of comprehension regarding consent may exist fifty-fifty larger. Therefore, a lack of relevant research in therapeutic clinical settings constitutes a remarkable gap in a crucial aspect of ethically viable medical practice.

Conclusion

Nosotros plant that the level of comprehension regarding informed consent components, such every bit voluntary participation, blinding, and freedom to withdraw, was low, being understood past only one-half of the patients. This seriously undermines the ethical foundations of current practices for obtaining consent in clinical trials, potentially besides challenging the standard arroyo to safeguarding patients' autonomy in ordinary medical settings.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are bachelor from the corresponding writer on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- IC:

-

Informed consent

- IDU:

-

Injection drug users

- MEDLINE:

-

Medical Literature analysis and retrieval system online (a database)

- MeSH:

-

Medical bailiwick headings

- Embase:

-

Excerpta Medica database

References

-

Agozzino E, Borrelli Southward, Cancellieri Chiliad, Carfora FM, Di Lorenzo T, Attena F. Does written informed consent adequately inform surgical patients? A cross sectional study. BMC Med Ethics. 2019;20(i):1.

-

Neff MJ. Informed consent: what is it? Who can give it? How exercise we amend it? Respir Intendance. 2008;53(ten):1337–41.

-

Durand MA, Moulton B, Cockle E, Mann M, Elwyn G. Can shared controlling reduce medical malpractice litigation? A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:167.

-

Manti Southward, Licari A. How to obtain informed consent for research. Exhale (Sheffield, England). 2018;14(ii):145–52.

-

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA argument for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. Bmj. 2009;339:b2700.

-

Minnies D, Hawkridge T, Hanekom W, Ehrlich R, London 50, Hussey Yard. Evaluation of the quality of informed consent in a vaccine field trial in a developing country setting. BMC Med Ethics. 2008;nine:xv.

-

Schumacher A, Sikov WM, Quesenberry MI, Safran H, Khurshid H, Mitchell KM, et al. Informed consent in oncology clinical trials: a Brownish Academy Oncology Enquiry Group prospective cross-sectional pilot study. PLoS One. 2017;12(two):e0172957.

-

Chu SH, Jeong SH, Kim EJ, Park MS, Park Thou, Nam M, et al. The views of patients and healthy volunteers on participation in clinical trials: an exploratory survey study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(4):611–nine.

-

Chaisson LH, Kass NE, Chengeta B, Mathebula U, Samandari T. Repeated assessments of informed consent comprehension amid HIV-infected participants of a iii-year clinical trial in Republic of botswana. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e22696.

-

Ellis RD, Sagara I, Durbin A, Dicko A, Shaffer D, Miller L, et al. Comparing the understanding of subjects receiving a candidate malaria vaccine in the United States and Mali. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83(iv):868–72.

-

Bergenmar G, Molin C, Wilking Due north, Brandberg Y. Knowledge and agreement amid cancer patients consenting to participate in clinical trials. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(17):2627–33.

-

Bertoli AM, Strusberg I, Fierro GA, Ramos M, Strusberg AM. Lack of correlation between satisfaction and knowledge in clinical trials participants: a pilot written report. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28(six):730–6.

-

Krosin MT, Klitzman R, Levin B, Cheng J, Ranney ML. Bug in comprehension of informed consent in rural and peri-urban Mali, Westward Africa. Clin Trials. 2006;3(3):306–13.

-

Criscione LG, Sugarman J, Sanders L, Pisetsky DS, St Clair EW. Informed consent in a clinical trial of a novel treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49(3):361–7.

-

Pope JE, Tingey DP, Arnold JM, Hong P, Ouimet JM, Krizova A. Are subjects satisfied with the informed consent process? A survey of research participants. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(4):815–24.

-

McNally T, Grigg J. Parents' agreement of a randomised double-blind controlled trial. Paediatr Nurs. 2001;13(4):11–4.

-

Itoh One thousand, Sasaki Y, Fujii H, Ohtsu T, Wakita H, Igarashi T, et al. Patients in stage I trials of anti-cancer agents in Japan: motivation, comprehension and expectations. Br J Cancer. 1997;76(1):107–13.

-

Harrison K, Vlahov D, Jones One thousand, Charron Thou, Clements ML. Medical eligibility, comprehension of the consent process, and retentiveness of injection drug users recruited for an HIV vaccine trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;10(three):386–90.

-

Ponzio M, Uccelli MM, Lionetti S, Barattini DF, Brichetto G, Zaratin P, et al. User testing as a method for evaluating subjects' understanding of informed consent in clinical trials in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;25:108–11.

-

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Higgins JPT. Tools for assessing hazard of reporting biases in studies and syntheses of studies: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2018;eight(iii):e019703.

-

Tam NT, Huy NT, Thoa le TB, Long NP, Trang NT, Hirayama Yard, et al. Participants' understanding of informed consent in clinical trials over 3 decades: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2015;93(iii):186–98h.

-

Falagas ME, Korbila IP, Giannopoulou KP, Kondilis BK, Peppas Yard. Informed consent: how much and what practice patients understand? Am J Surg. 2009;198(three):420–35.

-

Idanpaan-Heikkila JE. WHO guidelines for good clinical practice (GCP) for trials on pharmaceutical products: responsibilities of the investigator. Ann Med. 1994;26(2):89–94.

Acknowledgements

Not applicative.

Funding

This inquiry did not receive whatever specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-for-profit sectors.

Writer data

Affiliations

Contributions

T.Southward. conceived this written report, decided on the framework for analysis, carried out the literature searching and assay, and drafted the manuscript. K.S. decided on the framework for analysis, carried out the literature searching and analysis, and drafted the manuscript. All authors take read and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they accept no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher'southward Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is licensed under a Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits apply, sharing, accommodation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were fabricated. The images or other tertiary party material in this commodity are included in the commodity'south Artistic Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended utilize is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, yous volition need to obtain permission straight from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/iv.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data fabricated available in this commodity, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

Most this article

Cite this article

Pietrzykowski, T., Smilowska, K. The reality of informed consent: empirical studies on patient comprehension—systematic review. Trials 22, 57 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-020-04969-westward

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/s13063-020-04969-westward

Keywords

- Informed consent

- Clinical trials

- Medical exercise

- Police

- Ethics

- Comprehension

- Health care quality

- Autonomy

Source: https://trialsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13063-020-04969-w

0 Response to "Designing and Reviewing Informed Consent in Clinical Trials Pdf"

Post a Comment